The Evolution of Immigration Reform in the U.S.: A Century of Change and Challenges

6/17/20254 min read

The Evolution of Immigration Reform in the U.S.: A Century of Change and Challenges

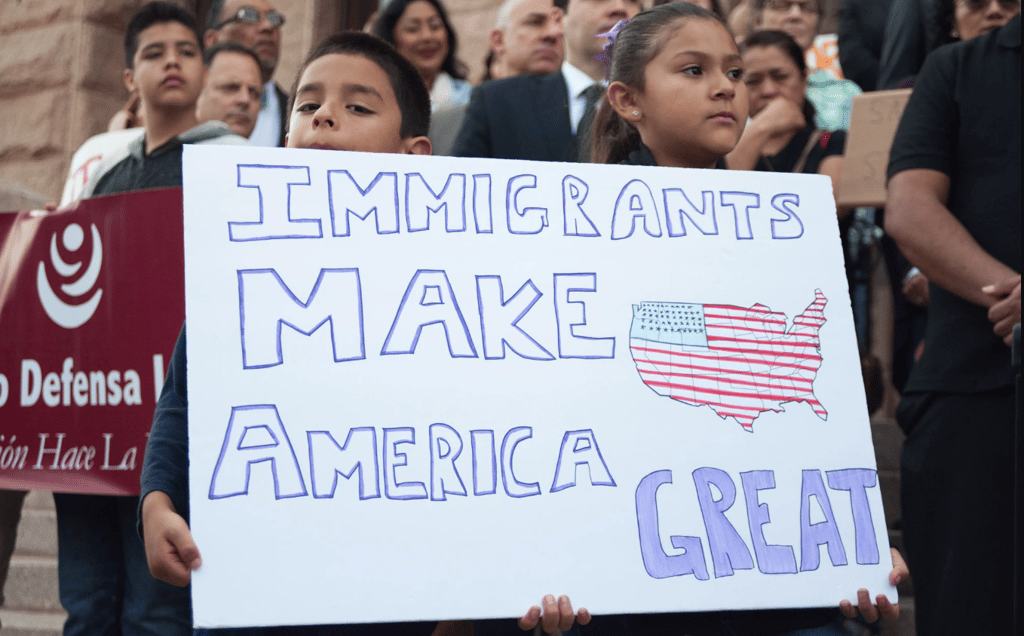

Introduction: A Nation Shaped by Immigration

The United States, often called a nation of immigrants, has a complex history of immigration reform driven by economic needs, social attitudes, and political priorities. From early open-border policies to restrictive quotas and modern debates over undocumented immigration, U.S. immigration laws have evolved dramatically. This analysis traces the key milestones in immigration reform, focusing on their impacts and the ongoing struggle to balance humanitarian values with enforcement. As debates continue in 2025, understanding this history offers critical context for addressing today’s challenges.

Early Foundations: Open Borders to Restriction

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the U.S. had minimal federal immigration controls, welcoming settlers to populate its vast lands. The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited citizenship to “free white persons” of “good character,” reflecting early racial biases. By the late 1800s, rising immigration and economic concerns prompted stricter laws. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first to ban a specific nationality, targeting Chinese laborers amid anti-Asian sentiment. The Immigration Act of 1891 centralized federal oversight, expanding excludable categories like polygamists and those with contagious diseases.

The early 20th century saw further restrictions. The Immigration Act of 1917 imposed literacy tests and created an “Asiatic Barred Zone,” excluding most Asian immigrants. The 1924 Immigration Act introduced national origins quotas, capping immigration at 2% of each nationality’s 1890 U.S. population, favoring Western Europeans and sharply limiting Southern and Eastern Europeans and Asians. These quotas, rooted in nativism, shaped immigration until the mid-20th century.

Mid-20th Century: Shifting Priorities

Post-World War II, global humanitarian needs and Cold War politics prompted reform. The 1943 Magnuson Act repealed Chinese exclusion, allowing limited Chinese immigration, while the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) eliminated race-based citizenship barriers but retained national origins quotas. The INA also prioritized skilled immigrants and family reunification, setting the stage for modern policies.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, or Hart-Celler Act, was a pivotal reform, abolishing national origins quotas and establishing a preference system based on family ties and skills. This shift diversified immigration, increasing flows from Asia, Latin America, and Africa, though some critics argue it altered traditional demographics. The act capped Western Hemisphere immigration for the first time, affecting Mexico, and set a global visa limit, shaping today’s legal immigration framework.

Late 20th Century: Enforcement and Amnesty

By the 1980s, undocumented immigration, estimated at 2–4 million, became a flashpoint. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, signed by President Reagan, was a landmark compromise. It legalized about 2.7 million undocumented immigrants who arrived before 1982, introduced employer sanctions for hiring unauthorized workers, and bolstered border enforcement. However, weak enforcement and no legal pathway for low-skilled workers led to continued illegal immigration, with nearly 12 million undocumented workers by the 2000s, 70% from Mexico.

The 1990s saw heightened enforcement. The 1990 Immigration Act increased legal immigration and created Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for those fleeing conflict or disasters. However, the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) expanded deportable offenses, introduced expedited removal, and penalized employers, shifting focus to enforcement. Post-9/11, the 2002 Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act and 2005 REAL ID Act tightened visa processes and border controls, reflecting national security concerns.

21st Century: Stalled Reform and Executive Action

Comprehensive immigration reform has eluded Congress since IRCA. The 2005 Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act and 2013 Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act proposed paths to citizenship, guest worker programs, and stronger enforcement but failed to pass. The 2013 bill, passed by the Senate 68–32, included a citizenship path for 11 million undocumented immigrants but died in the House.

In the absence of legislative progress, presidents have used executive actions. In 2012, President Obama introduced Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), protecting over 800,000 young undocumented immigrants from deportation and granting work permits. In 2014, he expanded DACA and proposed Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA), but both faced legal challenges, and DACA stopped accepting new applicants by 2022. As of 2025, DACA’s future remains uncertain amid ongoing litigation.

Recent policies reflect polarized priorities. President Trump’s administration (2017–2021) emphasized enforcement, expanding border walls, restricting asylum, and issuing travel bans on certain countries. President Biden reversed many of these policies, expanding TPS and reducing interior enforcement, but faced record border crossings, prompting new asylum restrictions. Public sentiment, as seen on X, ranges from calls for stricter enforcement to demands for humanitarian reform.

Impact and Ongoing Challenges

Immigration reform has shaped America’s demographic, economic, and social landscape. The 1965 act diversified the population, with immigrants comprising 14% of the U.S. in 2022. IRCA’s amnesty integrated millions but failed to curb future unauthorized immigration. DACA empowered Dreamers but left them in limbo without a citizenship path. Enforcement-focused laws like IIRIRA increased deportations, straining communities and economies.

Today’s debates center on border security, legal pathways, and undocumented immigrants’ status. A 2024 Pew poll found 60% of voters support allowing undocumented immigrants to stay, with 36% favoring a citizenship path, but bipartisan consensus remains elusive. Economic arguments highlight immigrants’ contributions—filling labor gaps and paying billions in taxes—while critics cite costs, estimated at $338.3 billion by some, though contested.

Conclusion: Toward a Balanced Future

The history of U.S. immigration reform reflects a tension between openness and control, inclusion and enforcement. From the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to the 1965 Hart-Celler Act and 1986 IRCA, each reform addressed immediate needs but often created new challenges. As America grapples with record migration and political divides in 2025, comprehensive reform—balancing humanitarian goals, economic needs, and security—remains critical. Understanding this history equips us to navigate the path forward.

Thought-Provoking Questions:

How can the U.S. create a sustainable immigration system that addresses both humanitarian and enforcement concerns?

What lessons from past reforms, like IRCA or the 1965 act, could guide future legislation?

How should public sentiment, as seen in polls and on platforms like X, influence immigration policy?

Sources: This analysis draws on data from Pew Research Center, USCIS, Migration Policy Institute, and other reputable sources, supplemented by sentiment on X. For further details, visit uscis.gov or pewresearch.org.

hello@boncopia.com

+13286036419

© 2025. All rights reserved.